Mathematics Outreach

Over the past few years I’ve given a number of general audience talks for high school and college students. I’m sharing a few below.

Geometry of vision

Which of the following viewpoints of the tiled floor would be easiest to draw?

Surprisingly, the third is easiest: you don’t need to take a single measurement, in contrast to the first two! In fact, all you need to draw it is your pencil and an unmarked scale (or straightedge) for connecting points. You could say this third viewpoint is actually in the most general position, demonstrated by the useful property that any set of parallel lines appears to converge to a point at infinity!

And that’s the basic principle of perspective drawing: parallel lines appear to converge in the distance. Looking at examples, it is easy to see that pictures drawn “in perspective” correctly model our vision, while pictures that are not drawn “in perspective” fail to do so. But why is this the case? Namely, why is it that when we look at two parallel lines in space, we actually observe them converging to the same point? And why do different families of parallel lines seem to converge to different points?

For the sides to this talk click here.

For the worksheet click here.

This talk was partly based on John Stillwell’s excellent book The Four Pillars of Geometry.

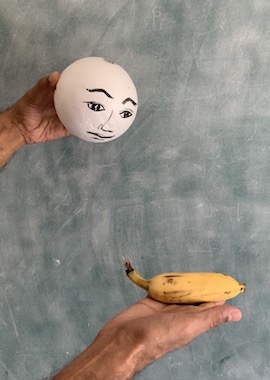

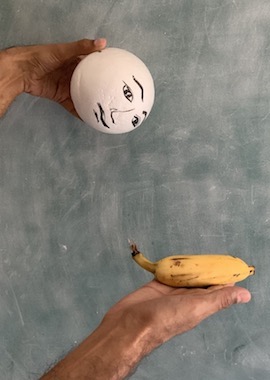

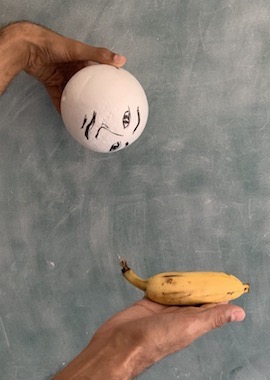

Getting your head around spatial rotations

Every time you move your head you are rotating the space around you. And you do this constantly, every day, every minute, while you’re awake and even while you’re asleep. But how well do you really know the collection of rotations of three dimensional space?

With the help of a spherical puppet we’ll try to count the dimensions of the space of rotations, and then try to understand the shape of this rather perplexing and counter-intuitive space: if you wear a belt or have a long plait of hair it’ll come in handy here!

To build your intution for this space, you will construct a spherical puppet of your own, which you will send on a journey through some very strange loops! Finally, we’ll enlist the aid of the Quaternion numbers to definitively know our place in the space of rotations.

For the sides to this talk click here.

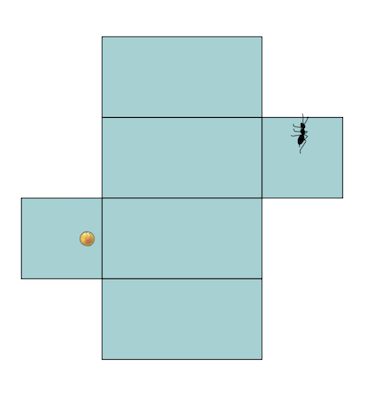

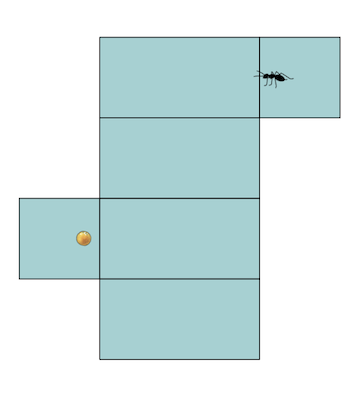

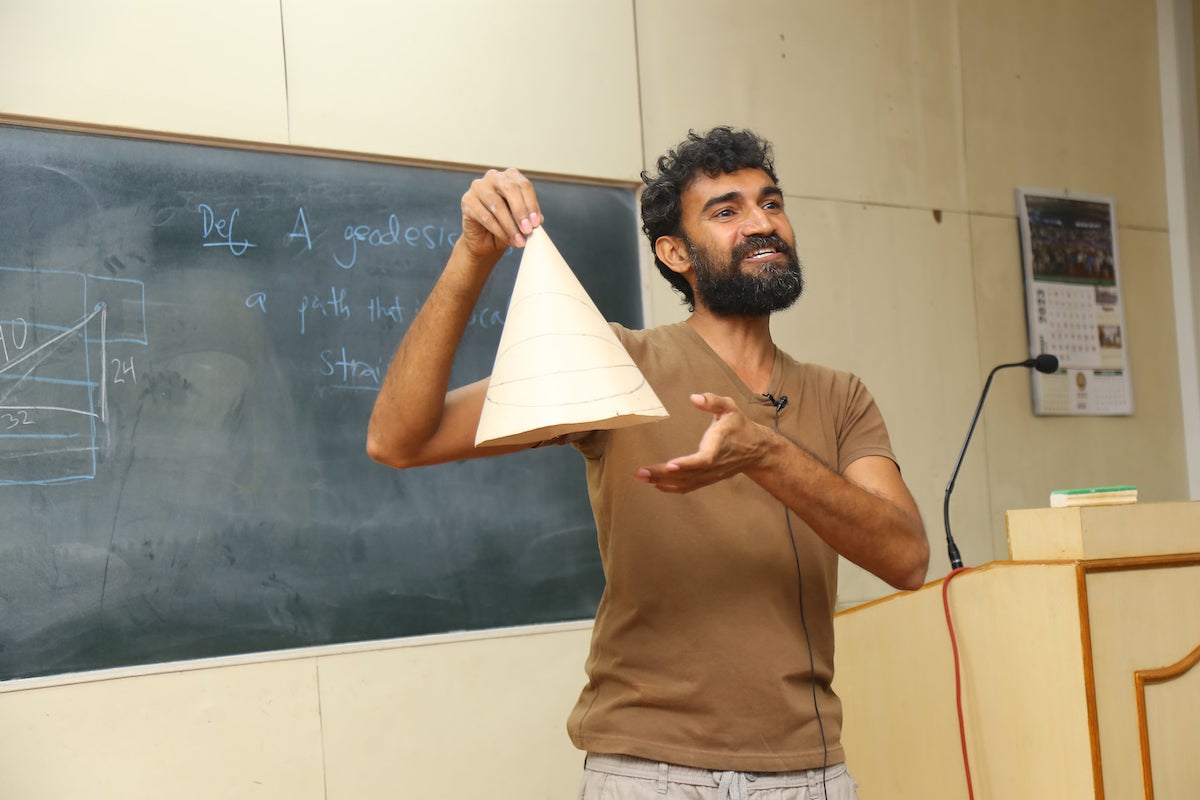

The geodesic journey of the hungry ant

When you leave your laddu unattended, what typically happens? Yes, here come the ants! They are true masters of finding the shortest, fastest path to food. In a plane, that may not sound so impressive, since the shortest path is just the unique straight line connecting the ant to the food. But ants can find food on any surface you can imagine.

This talk is heavy on physical props. Beginning with boxes, and then progressing to cones, cylinders, spheres, and hyperbolic planes, we explore how shortest paths are always locally straight, or geodesic, but their appearance often defies our expectations! Moreover geodesic paths are not always the shortest! I gave this talk at Forays, IIT Madras, in 2023. For the worksheet click here.

The talk is partly based on the book The Heart of Mathematics by Ed Burger and Michael Starbird, and the images in my worksheet are copied directly from there.

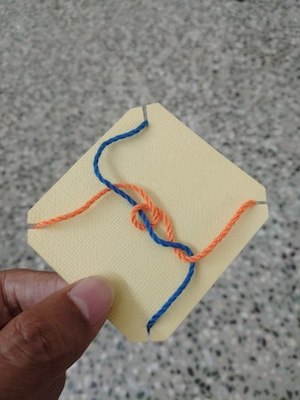

Untangling a knot, with numbers!

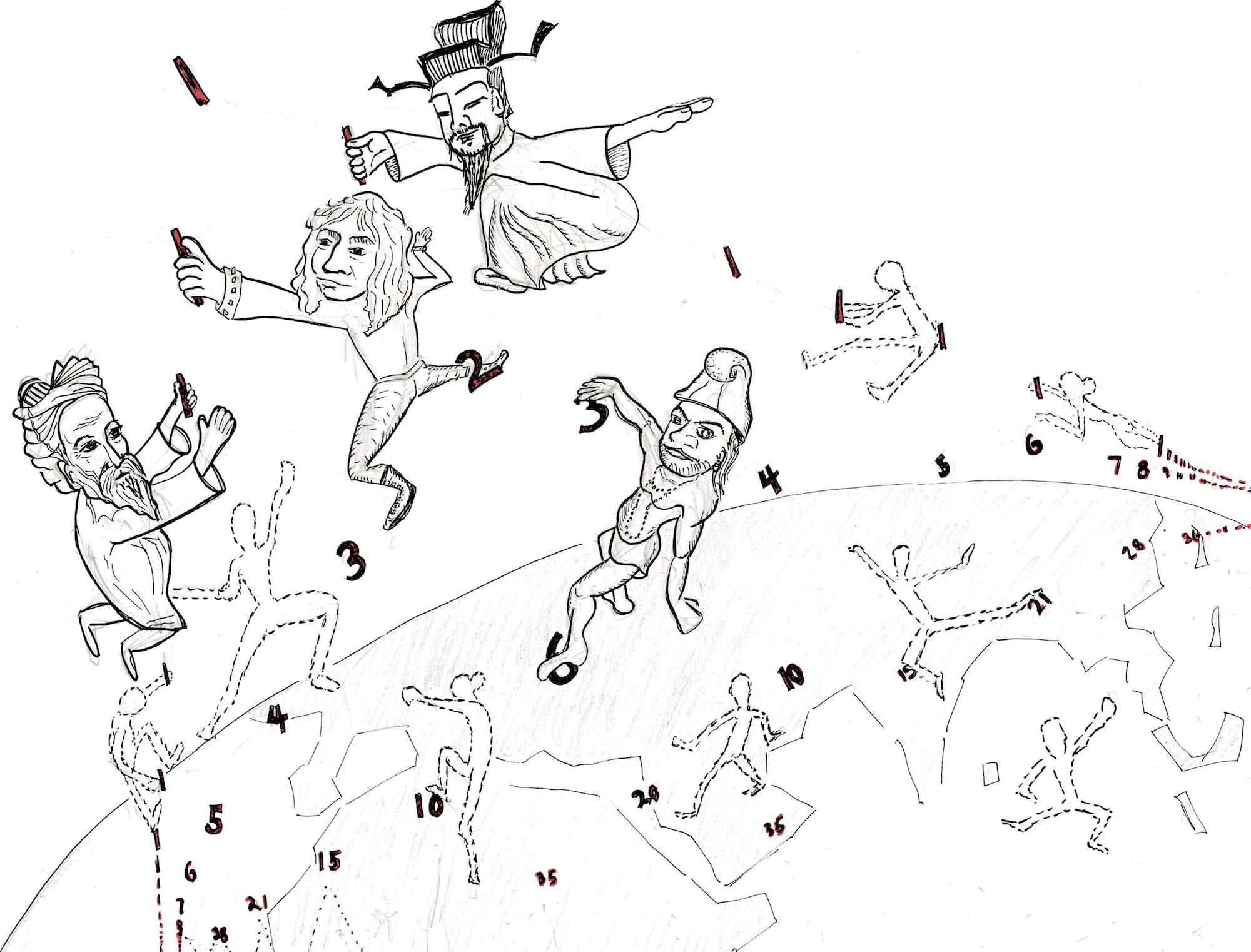

Have you ever tied a knot? Maybe while lacing your shoelaces? Or to keep a bag from opening? But did you know that knots have a secret life? Knots can behave like some mathematical objects you already know quite well. And knots will help you understand those familiar objects in a surprising new way!

The familiar objects in question are the rational numbers, and this activity explores a surprising correspondence between rational numbers and a special class of tangles. I facilitated this activity in Tamil at Kanita Kanagam, IMSc, in 2022. For the worksheet click here.

The talk is heavily based on the excellent writings and videos of Tom Davis and James Tanton, on the same topic, as well as videos by John Conway.

In search of a lost bicycle

Where has your bicycle gone? You can see tracks in the mud, but which direction are they going? If you could only determine the direction and follow the tracks, you just might find the bike itself. But is it even possible to do so?

For the worksheet click here.

For the press coverage of my talk in Dinamalar click here.

I gave this talk in Tamil to 150 school students as part of the Tamil language program kaNita-kAnakam at IMSc. It was largely based onthe Math Circle Session The Mathematics of Bicycle Tracks by James Tanton.

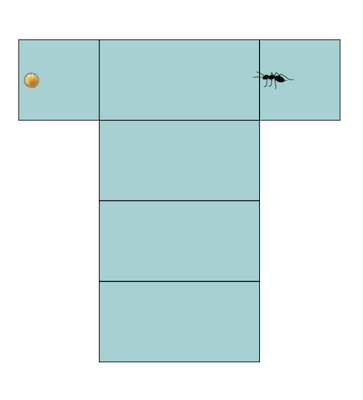

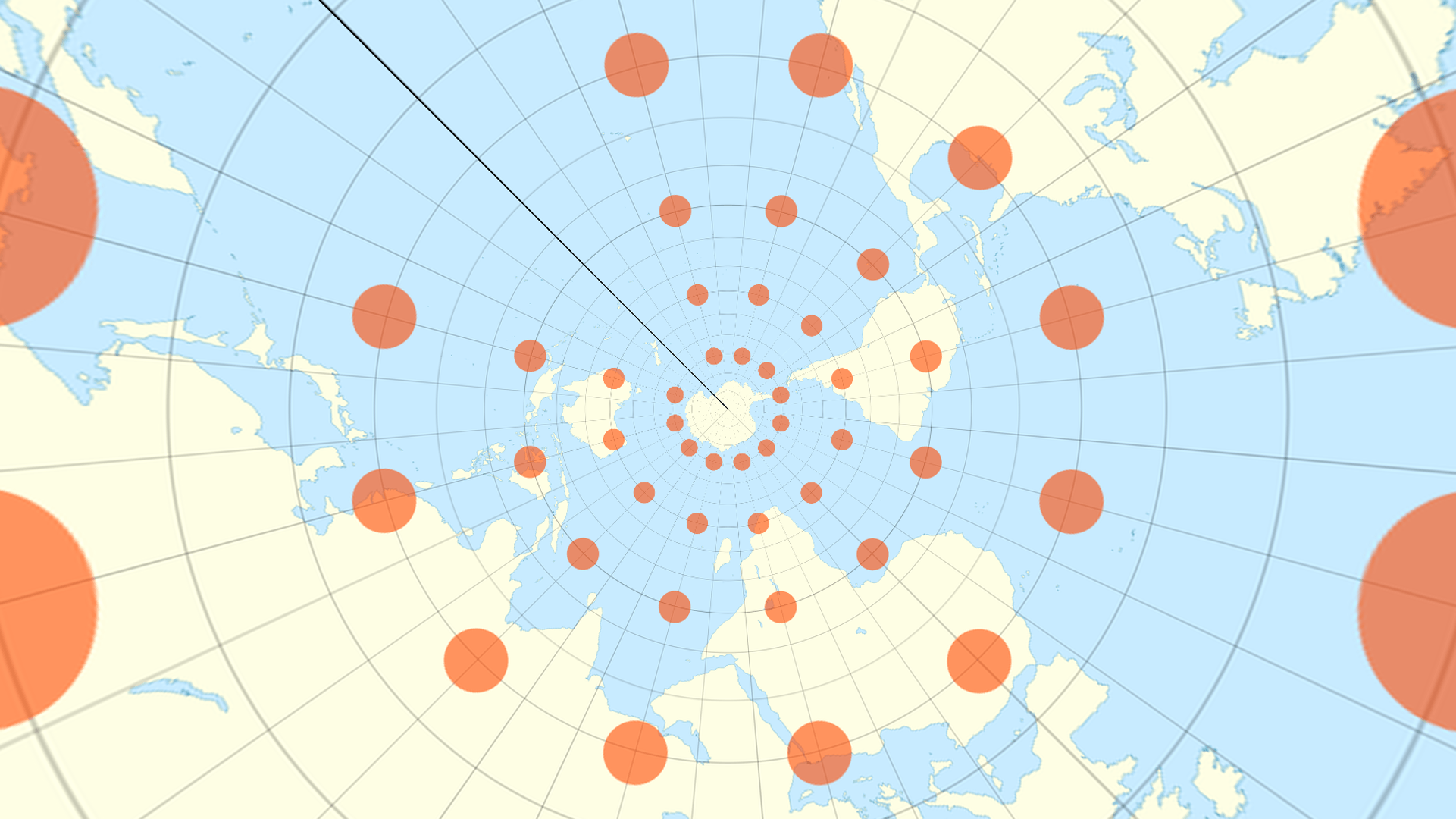

Do maps make the world go round?

Gauss’s Theorema Egregium tells us that the sphere and the plane have different curvatures, and as a consequence there can never be a perfect map of the surface of the Earth. However, it is not hard to construct a map that preserves other important features of our planet’s surface, such as local surface area, shortest path curves, or angles of intersections of curves (i.e. shape).

Because of Gauss’ Theorem, no map can accurately represent both area and shape. Yet despite this obstruction, people have come up with remarkable innovations, including a tetrahedral Earth that can be “unfolded” into an infinitely repeating, center-less map of Earth.

For the sides to this talk click here.

For the tetrahedron template click here.

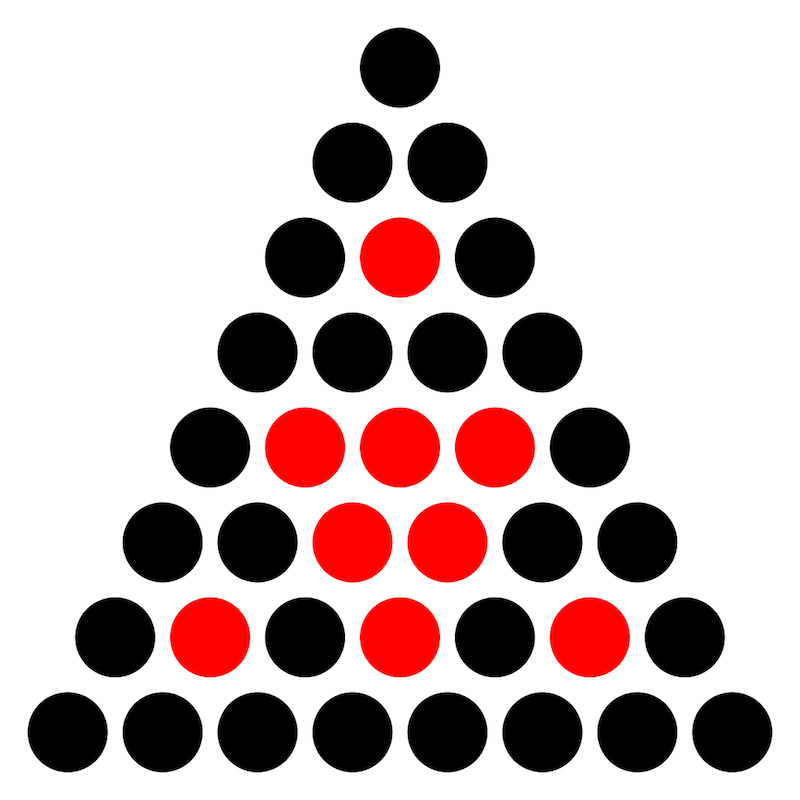

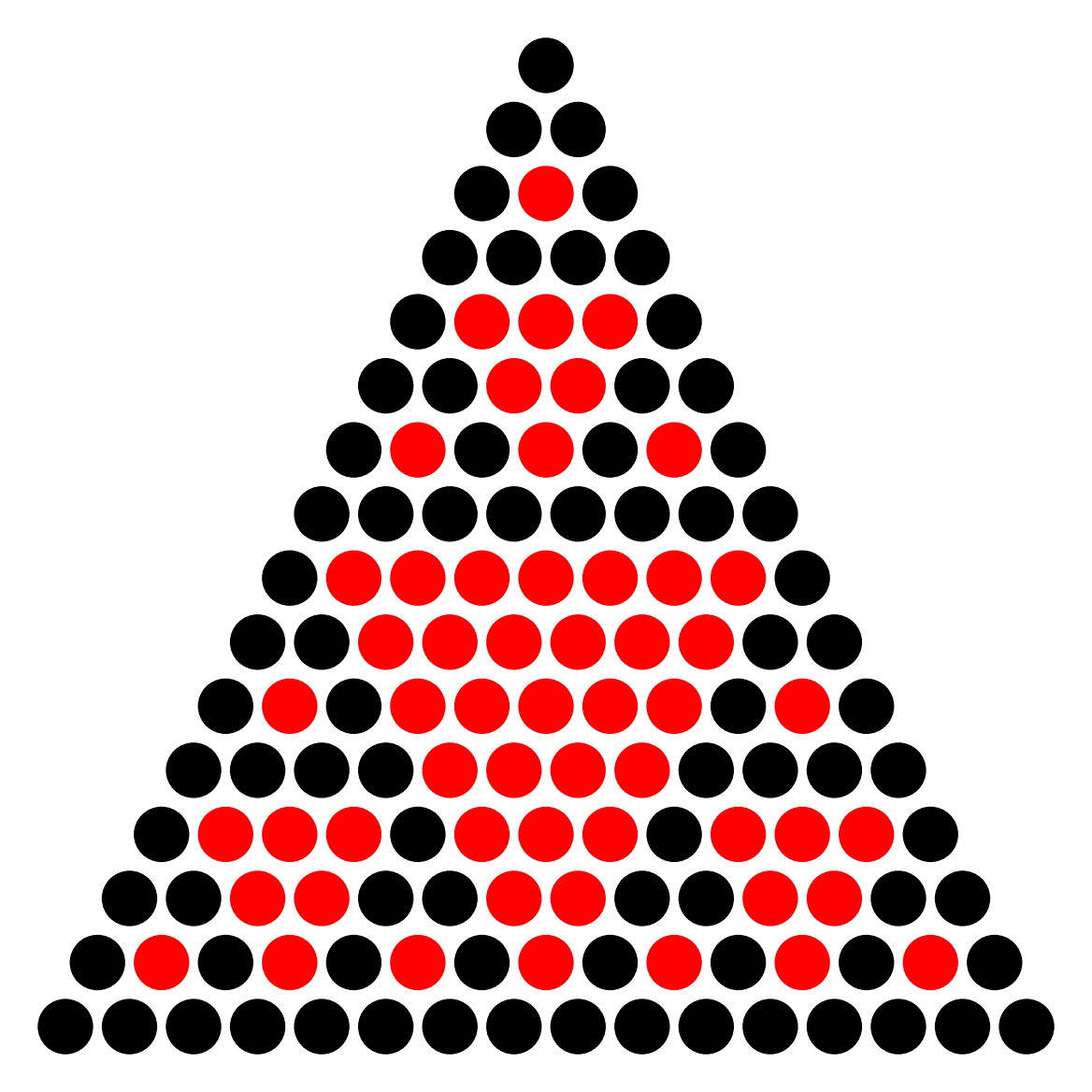

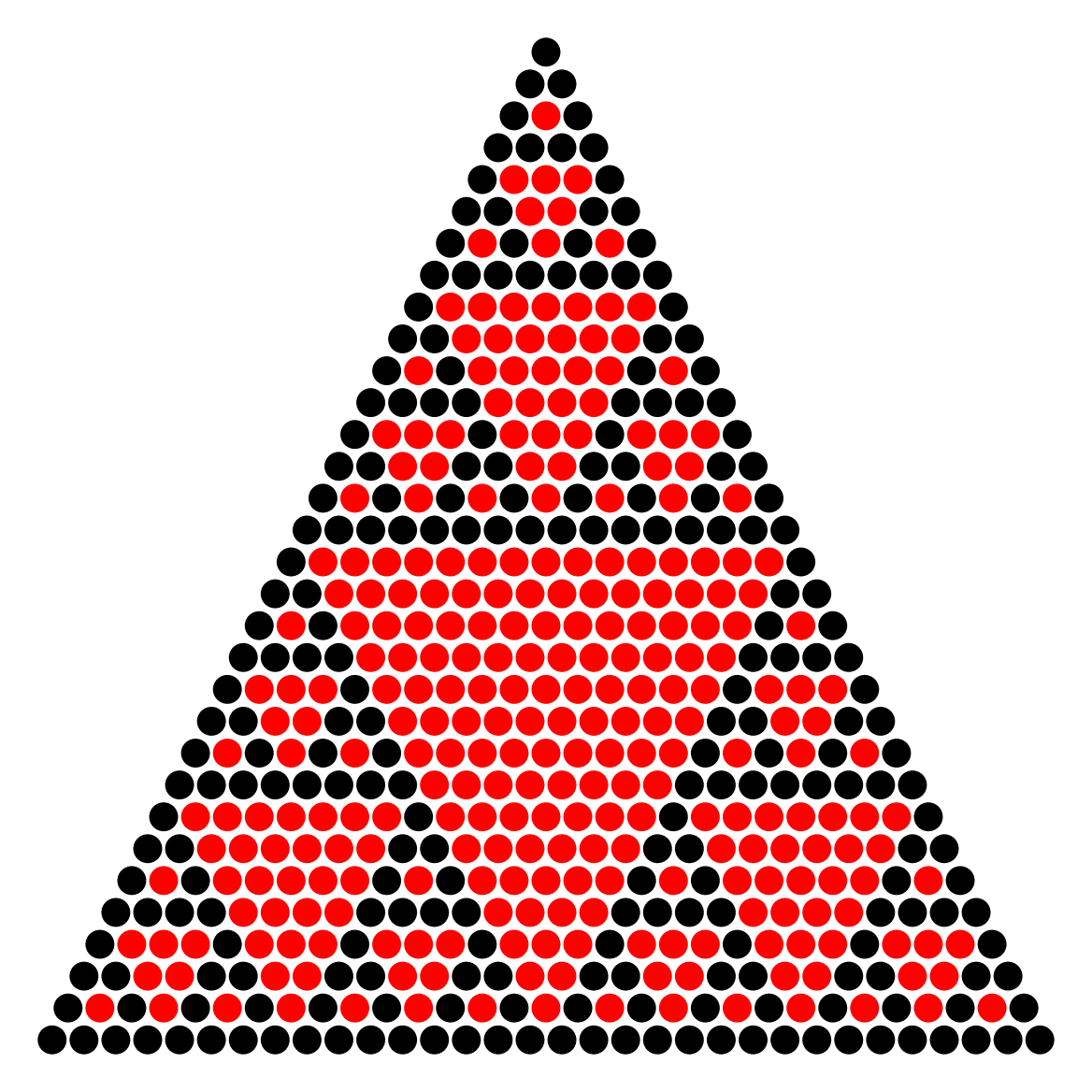

Pascal’s Triangle evened out

One of the most remarkable aspects of Pascal’s Triangle is how often it has appeared in different cultures and contexts and time periods. No person or society can claim ownership – it is a truly human invention!

As with many mathematical objects, some of the most interesting patterns in Pascal’s Triangle emerge only when you ‘forget’ much of what you know about it. To begin with, take a look at what happens when you examine just the odd entries of Pascal’s triangle.

And this is just the beginning – using modular arithmetic you can discover even more families of ‘self-similar’ fractals residing within.

For the sides to this talk click here.

To try coloring Pascal’s triangle yourself, you can use this blank template or this this numbered template

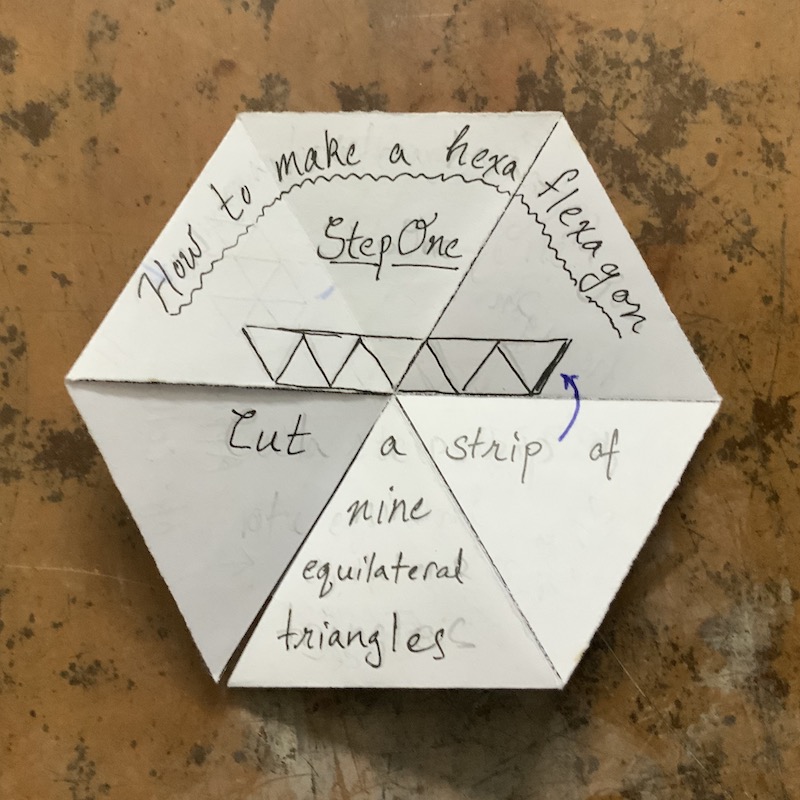

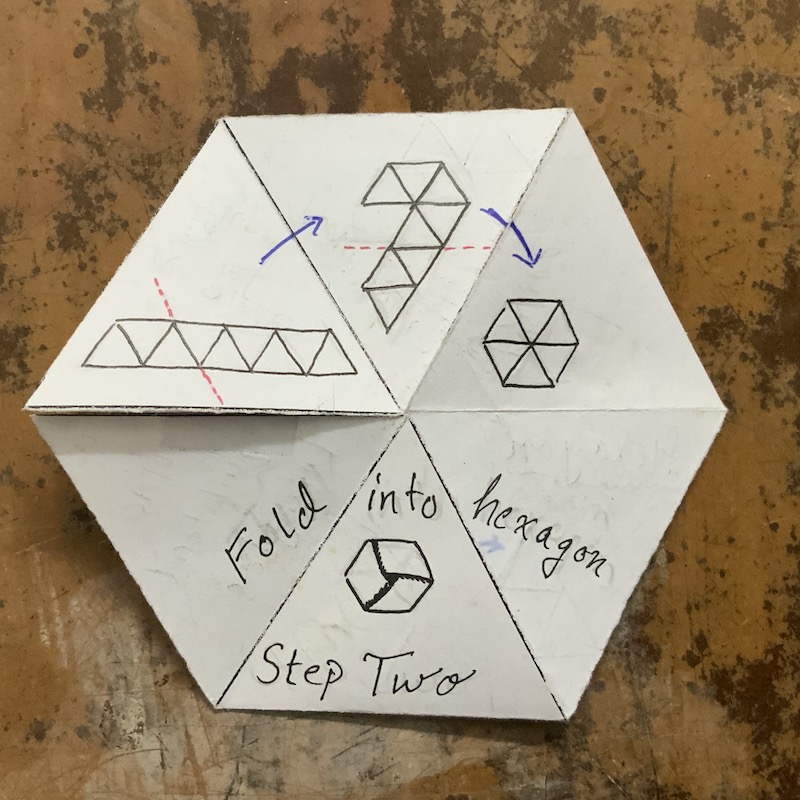

An invitation to hexaflexagate

A strip of paper and a bit of cello tape is all one needs to construct a hexaflexagon. Questions of a mathematical nature arise when you begin to examine the properties of your creation. And the answers to these questions may lead to new construction ideas!

For the sides to this talk click here.

For large triangle paper click here.

For small triangle paper click here.